A Gaussian Process Classifier Made From Scratch, in PyTorch

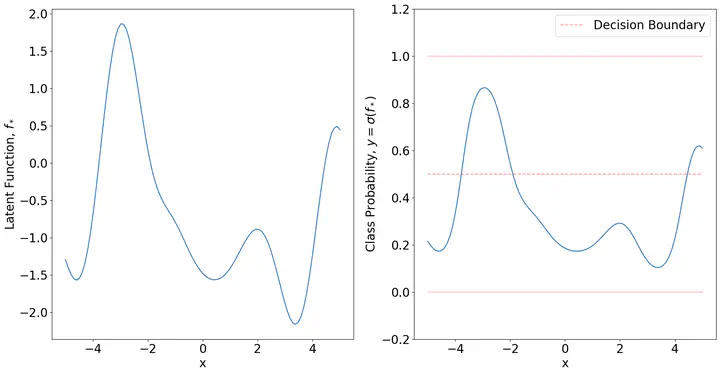

A prior sample of a GP logistic regressor.

A prior sample of a GP logistic regressor.This notebook walks through a basic example of Gaussian Process classification from scratch. Theory and code included. This tutorial follows mostly Rasmussen and Williams as well as sections in Bishops PRML pertaining to the subject.

Imports

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import torch as torch

import torchvision.datasets as datasets

from torchvision.transforms import ToTensor

import pandas as pd

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader

import matplotlib

from scipy.optimize import minimize

Helpful Functions

# This class interacts with PyTorch's DataLoader.

class data(Dataset):

def __init__(self, X, Y):

self.X = X

self.Y = Y

if len(self.X) != len(self.Y):

raise Exception("The length of X does not match the length of Y")

def __len__(self):

return len(self.X)

def __getitem__(self, index):

# note that this isn't randomly selecting. It's a simple get a single item that represents an x and y

_x = self.X[index].unsqueeze(dim=0)

_y = self.Y[index].unsqueeze(dim=0)

return _x, _y

# Gaussian Process Squared Exponential Kernel

def K(X,Y,ℓ,w,σn = 1e-10):

scaledX = X/(np.sqrt(2)*ℓ)

scaledY = Y/(np.sqrt(2)*ℓ)

R = torch.cdist(scaledX, scaledY, p=2)**2

return w*torch.exp(-R)+σn*torch.eye(len(X))

# Importing the MNIST dataset.

mnist_trainset = datasets.MNIST(root='./data', train=True, download=True, transform=ToTensor())

# Defines which two numbers to try and classify,

# This implementation is a binary classifier.

num1 = 2

num2 = 6

# Exclude all numbers in the lables that are not num1 or num2

labels = mnist_trainset.targets[((mnist_trainset.targets == num1) | (mnist_trainset.targets == num2))]

# Replace the labels with 0 and 1 for ease of training

labels[labels == num1] = 0

labels[labels == num2] = 1

# Exclude all numbers in the inputs that are not num1 or num2

inputs = mnist_trainset.data[((mnist_trainset.targets == num1) | (mnist_trainset.targets == num2))]

# Rescale the inputs to be [-1,1]

inputs = (inputs-(127.5))/127.5

Display the first few samples of the Dataset

fig,ax = plt.subplots(1,5,figsize=(20,10))

for i in range(5):

ax[i].imshow(inputs[i])

ax[i].set_title("Label: " + str(labels[i].item()))

ax[i].axis('off')

# The Dataloader class handles all the shuffles for you

# The batch size determine how many samples are shown to the GP, as well as the test dataset size.

loader = DataLoader(data(inputs,labels), batch_size=150,shuffle=True)

The fundamental assumption of GP classification is that of the latent function

matplotlib.rcParams.update({'font.size': 20})

Xs = torch.linspace(-5,5,100).unsqueeze(dim=0).T

Kxx = K(Xs,Xs,1,2.35,0)

Fs = torch.from_numpy(np.random.multivariate_normal(np.zeros(len(Kxx)),Kxx.numpy()))

fig,ax = plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=(20,10))

ax[0].plot(Xs,Fs)

ax[0].set_ylim(min(Fs) - 0.2, max(Fs) + 0.2)

ax[0].set_ylabel('Latent Function, $f_\*$')

ax[0].set_xlabel('x')

ax[1].plot(Xs,torch.sigmoid(Fs))

ax[1].set_ylim(- 0.2, 1.2)

ax[1].set_ylabel('Class Probability, $y = \sigma(f_\*)$')

ax[1].set_xlabel('x')

ax[1].plot(Xs,np.zeros(len(Xs)),alpha = 0.25,color='r')

ax[1].plot(Xs,np.ones(len(Xs)),alpha = 0.25,color='r')

ax[1].plot(Xs,0.5*np.ones(len(Xs)),alpha = 0.4,color='r',linestyle='dashed',label='Decision Boundary')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

C:\Users\hsull\AppData\Local\Temp\ipykernel_16228\1858434126.py:4: RuntimeWarning: covariance is not positive-semidefinite.

Fs = torch.from_numpy(np.random.multivariate_normal(np.zeros(len(Kxx)),Kxx.numpy()))

Within GP classification we can treat the function

Where we can then use Bayes Law to rewrite the function

With the distribution of

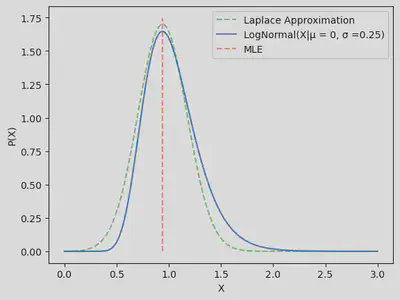

This all seems nice and dandy, however we have a lack of computability of the first and last function listed here. Both of the likelihoods are non gaussian and leave a lot to be desired when we want to actualy compute their integrals. This notebook uses the Laplace approximation to aquire an analytic approximation to the logistic GP. What exactly is the laplace approximation? Consider a log-normal probability density with

matplotlib.rcParams.update({'font.size': 10})

X = torch.linspace(0.001,3,200).unsqueeze(dim=0).T

σ = 0.25

μ = 0

P_X_LN = 1/(σ*X*np.sqrt(2*torch.pi))*torch.exp(-(torch.log(X) - μ)**2/(2*σ**2))

f = lambda x: -np.log(1/(σ*x[0]*np.sqrt(2*np.pi))*np.exp(-(np.log(x[0]) - μ)**2/(2*σ**2)))

out = minimize(f,method = 'L-BFGS-B', x0 = [2])

σ_Laplace = np.sqrt((out['hess_inv']).todense())

plt.plot(X,1/(σ_Laplace*np.sqrt(2*np.pi))*np.exp(-(X.numpy() - out['x'])**2/(2*σ_Laplace**2)),linestyle ='dashed',alpha = 0.5,color='g',label='Laplace Approximation')

plt.plot(X,P_X_LN,label='LogNormal(X|μ = 0, σ =0.25)')

plt.vlines(out['x'],0,max(P_X_LN)+0.1,linestyle ='dashed',alpha = 0.5,color='r',label='MLE')

plt.xlabel('X')

plt.ylabel('P(X)')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

The first step to actually computing the MAP estimate and the Hessian of the Laplace approximation is the distribution over the latent variable

Remebering that

Then differentiating with respect to

This function has a unique property. Due to the initital posterior being log-concave, that means there is a unique maximum as well as the Hessian being positive definite. At this point, there are a few choices for the likelihood. I am going to stick with the choice I made earlier, the classic sigmoid.

For ease of calculation I am going to define

Where

This results in an expression for the log probability, as well as its second derivative. As noted earlier, the is a convex problem. Meaning we can use the Newton-Raphson scheme to solve this. This implies an update equation of the form seen below.

This process has then been coded below, without a hyper parameter optimization.

# This defines the hyper parmeters of the the Gaussian Process,

# 784 in length due to the pixel count in an image.

ℓ = np.exp(2)*torch.ones(784)

w = np.exp(2.35)

# GPLR: Performs Gaaussian Process logistic regression on the inputs ϕ and their corresponding labels t.

# INPUTS

# ϕ := N x M matrix where N corresponds to the number of training samples and M is the dimensionality of the input vector

# t := N long vector of labels corresponding to training samples ϕ

# a_0 := N long vector of initial predictions for latent function values

# maxIterations := an integer corresponding to the max # of Newton-Raphson iterations.

# goalTolerance := a float corresponding to the stoppoing tolerance is max iterations isn't acheived.

#

# RETURNS

# a := N Long vector containing optimized latent function values for training set

# H := N x N matrix Hessian at MAP

# W := N x N matrix diagonal W matrix computed above, at the MAP

# grad := N long vector of the gradient of the likelihood at the MAP

# tolerance: Float of the final tolerance after Newton iteration.

def GPLR(Φ,t,a_0,maxIterations = 100,goalTolerance = 1e-4):

N = len(t) # Number of samples

A = len(a_0) # Dimensonality of space

a = a_0 # Initialize latent function guess to begin iterating

invCn = torch.linalg.inv(K(Φ,Φ,ℓ,w))# + torch.diag(torch.ones(A)*1e-4)) # evaluate kernel matrix

tolerance = 1

iteration = 0

while tolerance > goalTolerance and iteration < maxIterations:

# Computes needed quantities for update

σa = torch.sigmoid(a)

W = torch.diag(σa*(1 - σa))

gradE = t - σa -torch.matmul(invCn,a)

H = W + invCn

# Evaluate the update

update = torch.matmul(gradE,torch.linalg.inv(H))

# Update latent function values and use it to compute tolerance

a = a - update

tolerance = torch.sum(torch.abs(update))

iteration += 1

# Compute Hessian at the MAP for laplace approximation

σa = torch.sigmoid(a)

W = torch.diag(σa*(1 - σa))

grad = t - σa

H = W + invCn

return a,H,W,grad,tolerance

The last important aspect of GP classification is utilizing the latent function values to compute predicitions for a new test data point. We can take the expectation of the gaussian process to compute the expectation of

In the scope of this notebook, we are not interested in the variance of the predicitions. Just which prediction is the most optimal. For further reading on this, check out Rasmussen and Williams. Therefore we only need to plug this expectation through the sigmoid to get predictions. Hence:

# π_approx: Computes the MAP prediction of π_*

# X_test: J by M Matrix of the data points meant to be infered.

# X_train: N by M Matrix of the training data used to compute the latent function values

# grad: N long vector of the gradient of the likelihood at the MAP

def π_approx(X_test,X_train,grad):

Kid = K(X_test,X_train,ℓ,w)

fstar = torch.matmul(Kid,grad)

return torch.sigmoid(fstar)

# Use the data loader to create a set of training and testing datapoints for the GP

for i,(inputs,labels) in enumerate(loader):

# Save the training data set

if i == 0:

Y_Train = labels.squeeze(dim=1)

X_Train = inputs.squeeze(dim=1).flatten(start_dim=1)

# Save the testing data set

elif i == 1:

Y_Test = labels.squeeze(dim=1)

X_Test = inputs.squeeze(dim=1).flatten(start_dim=1)

# Break away

else:

break

# Compute latent function values MAP estimate along with other quantities.

a,H,W,grad,tolerance = GPLR(X_Train,Y_Train,torch.ones(len(X_Train)))

# Compute MAP π predictions.

π = π_approx(X_Test.unsqueeze(dim=0),X_Train,grad)[0]

# Use that to make a decision based of the 0.5 boundary

π[π >= 0.5] = 1

π[π < 0.5] = 0

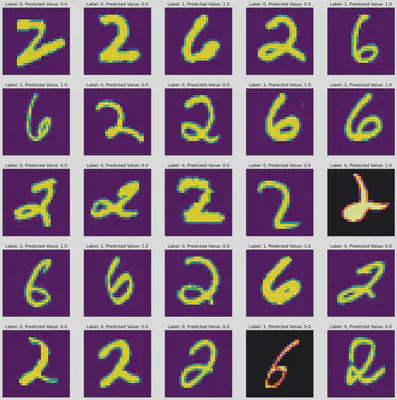

# Plots some results. Alternate inferno color means it failed.

fig,ax = plt.subplots(5,5,figsize=(20,20))

idx = 0

for i in range(5):

for j in range(5):

if Y_Test[idx].item() != π[idx].item():

ax[j][i].imshow(X_Test[idx].reshape(28,28),cmap="inferno")

else:

ax[j][i].imshow(X_Test[idx].reshape(28,28))

ax[j][i].set_title("Label: " + str(Y_Test[idx].item()) + ", Predicted Value: " + str(π[idx].item()))

ax[j][i].axis('off')

idx+=1

plt.show()

print("% Predictive Acccuracy: ",100 - 100*(torch.sum(torch.abs(π - Y_Test))/len(π)).item())

% Predictive Acccuracy: 94.66666653752327